The Taste of My Childhood: Sonoko Sakai

What culinary authority Sonoko Sakai ate when she was growing up in Tokyo, Mexico City, New York, and Kamakura—plus her recipe for Sweet Potato + Black Sesame Onigiri

Hi friends,

So much of our comfort as adults is shaped by the sensory experiences of childhood—the rare smell of rain on Southern Californian asphalt, the opening bars of Blackstreet’s peerless 1996 classic No Diggity, and, of course, the food. Though feeding our kids can feel at times like an exercise in neuroticism (Is there enough iron in that? How about protein?), and at times like drudgery (Do they really have to eat again?), it’s easy to forget that we’re also forming memories of food that our kids will carry with them for their whole lives. We say this not to terrify you, but to reconnect you to the heart of what it is to feed your family. It’s not the complicated recipes that your kids will remember, it’s the simple way you do things—shake up a jar of salad dressing, say, or swirl a knob of butter into a sauce—that will transport them back home.

We wanted to better understand how the foods of our childhood shape how we think about and relate to food as adults, but we also wanted a lens onto what kids are eating in different cultures around the world. Our geography, alone, shouldn’t limit the way we engage with cooking and eating—and yet, it so often does! With this new monthly column, ‘The Taste Of My Childhood,’ we’ll be asking people we admire about the foods that shaped their early years and what distinguished their family table.

Fanny met our first contributor, Sonoko Sakai, in the pages of her wonderful cookbook, Japanese Home Cooking: a gateway to the kind of cooking she had always wanted to do at home but needed some hand-holding (and inspiration) to actually start. Sonoko, who was born in New York and raised in a handful of cities including Tokyo, Kamakura, Mexico City, and San Francisco, cooks in a way that reflects her multicultural upbringing. When she was 9, her family returned to Japan and lived in the ancient capital of Kamakura, near her grandmother, a wonderful cook and teacher who would walk her down to the beach to buy fish directly from the fishermen. This experience is what prompted Sonoko’s epiphany about food (and also what inspired her illustrated children’s book, Mai and the Missing Melon.)

Now based in Los Angeles, Sonoko writes about Japanese cuisine, teaches culinary workshops and makes and sells an assortment of Japanese pantry products, including her incredible curry spice mix and unrivaled miso. A year ago, Fanny was lucky enough to attend one of Sonoko’s in-person cooking workshops at her home. It was in this workshop—in which Fanny learned to make buckwheat soba, Japanese curry and tamagoyaki (recipe coming later this week!)—that she fell truly in love with Sonoko’s taste and culinary style. Much of what distinguishes her cooking is elaborated in her most recent book, Wafu Cooking, a redefinition of what Japanese cooking can be. Wafu (literally “Japanese style”) food describes an approach to cooking in which “fusion” carries none of its dubious connotations. Instead, Sonoko combines flavors, ingredients, and techniques from around the world, giving them a distinctly Japanese spin.

Below, Sonoko answers our questions about what it was like to grow up eating in her household, and how it shaped the way she thought about, and eventually pursued a life in, the world of food. (And when you’re done, you can learn more about her work here.)

Dig in—and let us know what you think about this new column!

Fanny + Greta

Walk us through a typical (food) day in your childhood: what was breakfast, lunch and dinner and who made it for you?

I grew up in a large family of 5 kids. We moved around a lot (Tokyo, NY, Los Angeles, Mexico City, SF, and Kamakura) so the food changed according to where we lived. My mother was adventurous when it came to cooking and eating, so she was encouraging us to try new foods. At home, my mother cooked 5 cups of rice everyday. She did all the cooking. Breakfast: Freshly cooked rice with scrambled egg and natto (fermented soybeans) seasoned with soy sauce and miso soup with tofu and wakame was my favorite breakfast, but we often had toast with jam and butter and maybe an egg. Sometimes, if we were lucky, we got a piece of Laughing Cow cheese. Lunch: Mother made fried rice with leftover rice or a bowl of noodles for lunch. During the school days growing up in Japan, I took a bento (with onigiri) to school or the school served us lunch like curry, stews and fried whale katsu! Dinner was vegetable soup (like a minestrone) with grilled fish (my favorite local catch of Kamakura was Spanish Mackerel and sardines), salad, rice and pickles. We rarely ate meat because it was expensive but when we did, it was usually Tonkatsu or Teppanyaki style beef or Sukiyaki.

What was the thing you most wanted to smell coming out of your childhood kitchen? (And what did you least want to smell?)

Smell of freshly baked bread or cake coming from my grandmother's kitchen (she lived next door in Kamakura- our houses were connected by a corridor). I didn't like hydrated Shiitake Mushroom broth and pickled daikon radish.

What—if anything—is considered baby food in your cuisine? Are there any rules or traditions for introducing food to a baby?

Pureed kabocha squash, sweet potato, banana, tofu, porridge. Children drink Amazake (fermented rice beverage). It's considered a healthy beverage for all ages.

What was considered food contraband in your childhood?

Food that was banned by my mother was ice cream or ice candy from the local store in Tokyo and Kamakura. Street food like tacos, fruit and vegetable stands, fried pork rind in Mexico city. I ate them any way.

With what food would you celebrate your birthday when you were growing up?

Strawberry or Peach short cake that my grandmother baked for me. She did it for all her grandchildren.

What’s the first step for someone looking to incorporate Japanese food into their family kitchen? Any dishes or ingredients that are the easiest to make—and easiest for potentially picky kids to like? In other words, what’s the gateway drug?)

Miso - sneak it in as a seasoning. Tofu in soups.

Other than yours, what books would you recommend to someone who was looking to learn more about Japanese cuisine?

What’s your version of Proust’s madeleine?

Grilled Spanish mackerel (preferably sun-dried) - reminds me of my childhood in Kamakura.

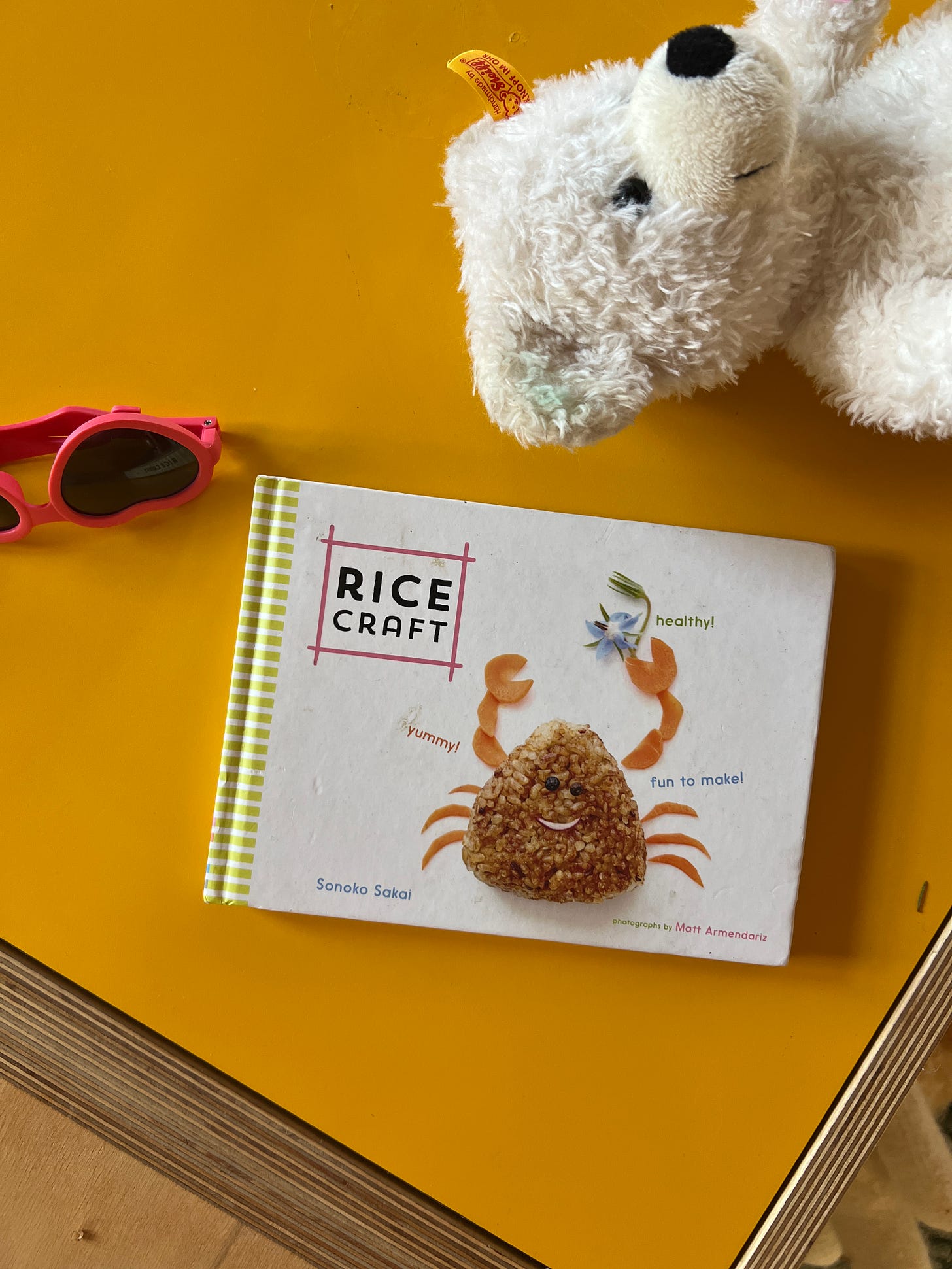

This is a classic onigiri from Sonoko’s darling little cookbook Rice Craft: Yummy! Healthy! Fun to Make! Published in 2016, the book features more than 30 recipes for onigiri with a range of delicious fillings as well as master recipes for cooking rice, plus extras to round out the meal: a miso soup to float the rice balls in, perfect soft eggs to wrap in rice, and pickled ginger to serve on the side. Designed to inspire new creations and teach kids and adults alike to make these creative treats, it’s a perfect homage to the foods Sonoko herself grew up eating and a mini masterclass in all things onigiri.

This Sweet Potato and Black Sesame Onigiri is made slightly modern with the use of butter. If you can't find satsumaimo (yellow sweet potato), use can use another variety of sweet potato.

Makes 12 onigiri

Ingredients

1½ cups [300 g] uncooked medium- or short-grain white rice, haiga rice, or mixed-grain rice

1¾ cups [420 ml] filtered water

2 tablespoon butter 8 oz [230 g] satsumaimo or other sweet potato, unpeeled, cut into ¼-in [6-mm] cubes

1 4-in [10-cm] piece dried konbu (kombu) seaweed

2 tablespoon sake

1 tablespoon mirin

2½ teaspoom sea salt

3 tablespoon black sesame seeds, toasted (*see note below)

1 sheet nori

The Method

Place the rice in a medium bowl and rinse under cool running water, using your hands to gently swish the grains for about 10 seconds. Drain completely.

Pour the filtered water into a heavy-bottomed pot with a tight-fitting lid. Add the rice and let soak for about 30 minutes.

In a frying pan over medium heat, melt the butter. Add the sweet potato and sauté until slightly brown, about 3 minutes.

Add the konbu, sake, mirin, sweet potato, and ½ tsp of the salt to the rice and stir until combined.

Place the pot, uncovered, over medium heat and bring to a boil. The water should bubble around the rim evenly. Cover the pot, turn the heat to very low, and cook, without peeking, for 20 minutes. Remove from the heat and, without opening the lid, let stand for 15 minutes.

Uncover the pot and gently fluff the rice with a rice paddle or wooden spoon. Re-cover and let stand for 5 minutes more. Remove the konbu (enjoy it as a snack). Fold the toasted sesame seeds into the rice, combining gently, without mashing the grains. When cool enough to handle, the rice is ready to make onigiri.

Cut the nori crosswise into twelve strips, each ¾ by 4 in [2 by 10 cm]; these are for wrapping the onigiri. Set aside in a dry place.

Have ready a large plate or cutting board to hold the finished onigiri. Prepare a small bowl of water for wetting your hands and a small bowl containing the remaining 2 tsp salt. Arrange near the plate.

Divide the rice into twelve equal portions. Scoop one portion into a small teacup or bowl. Moisten your hands with the water to keep the rice from sticking to them. Lightly dip the tips of the index, middle, and ring fingers of one hand into the bowl of water, then into the bowl of salt. Rub the salt onto your palms. You should have a light coating on your palms.

Gently tap the teacup or bowl to loosen the rice into your palm. Press gently into your palm, then use the index finger, middle finger, and thumb of your other hand to gently press the two ends of the ball to form a log, about 1½ in [4 cm] wide and 2½ in [6 cm] long. Now use your index finger, middle finger, and thumb to complete the log shape. Don't press too hard; the onigiri should be firm on the outside but soft and airy on the inside.

Place the finished onigiri on the prepared plate. Repeat with the remaining ingredients.

Hold an onigiri in one hand and wrap a piece of nori around it like a belt, starting at the center and wrapping around the log. Press gently to fix the nori in place. Repeat with the remaining onigiri and nori.

Eat immediately!

* A Note On Toasting Sesame Seeds:

To toast sesame seeds, put them in a wide frying pan over medium heat. Toast the seeds, stirring with a spatula, until they turn fragrant and a few seeds start to pop, about 2 minutes. Be careful not to burn the seeds. Remove from the heat and pour onto a metal baking sheet to let cool.

This is such a beautiful way to share memories of food! Reading about Sonoko's childhood made me nostalgic for my own early food memories. Thank you, Sonoko, for sharing the recipe; I can't wait to make the onigiri! xx